Miniature satellites to maximize global communication

Havel Liu is working on a project to revolutionize satellite systems, improving communications during natural disasters and providing a blueprint for receiving future interplanetary voicemails

Enlarge

Enlarge

Earthquakes level our cities. Wildfires consume our homes. Rockslides cuts off our escape routes. Hurricanes topple our buildings. Natural disasters can and do occur every day all over the world. When you’re caught in one, you may need to call for help, but most likely your cell phone will give you the worst of all possible messages: No Signal.

Cell phones are remarkable portable computers, but they’re not great during emergencies. Cell phones rely on land-based towers to transmit messages. Natural disasters often interfere with the towers and can cause them to go down completely.

That’s why emergency responders rely on satellite phones, which transmit signals through satellites orbiting the earth. But satellite communication is limited.

“Satellite antennas are very directed,” says Havel Liu, a CE and ME undergraduate student. “If you want to send or pick up a message, the satellite has to pass directly over the place you’re communicating with.”

Liu is part of a team that hopes to revolutionize how satellites operate, allowing for near-instant communication all over the globe.

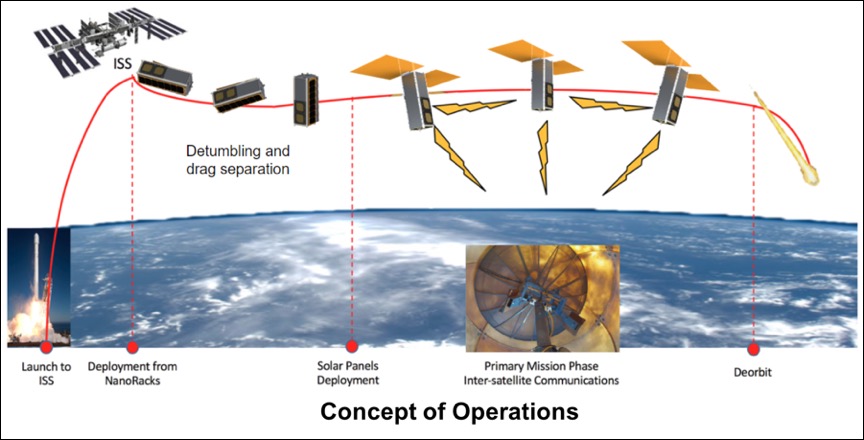

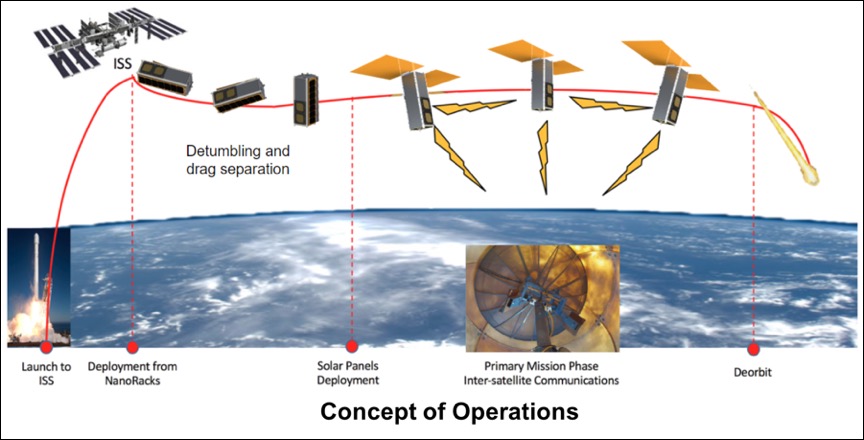

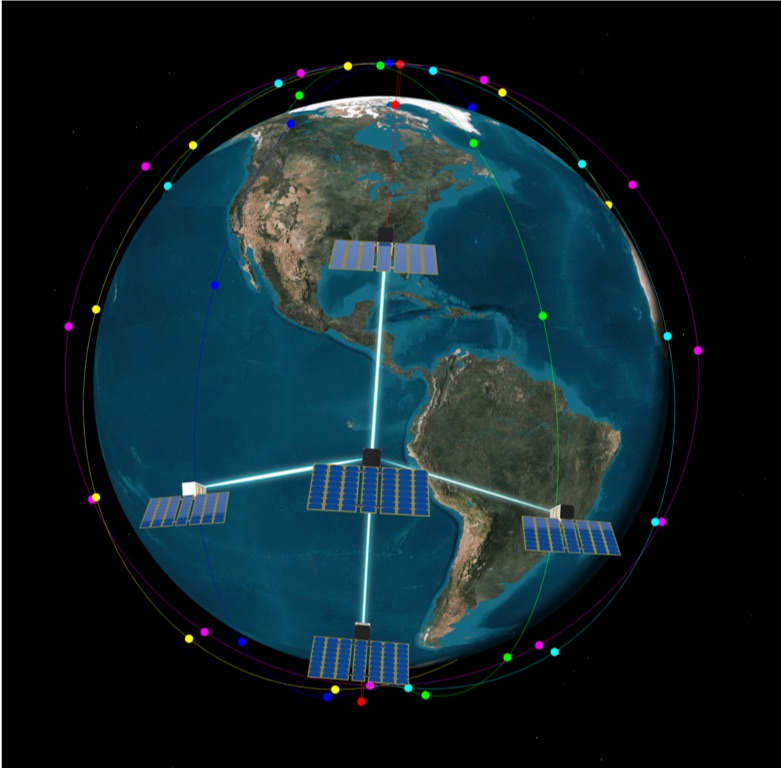

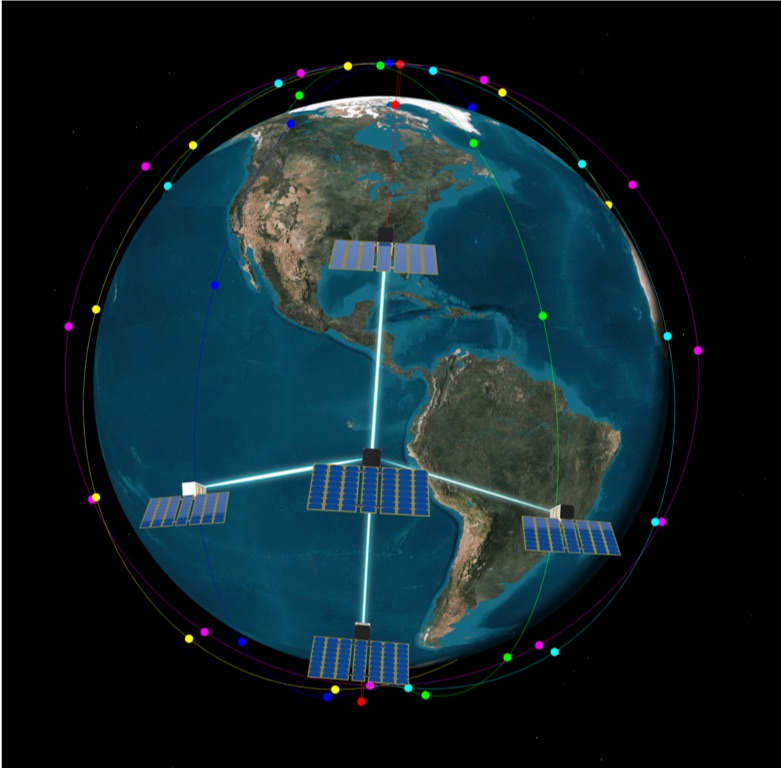

“Our idea,” Liu explains, “is to send 66 very small satellites into space that will cover 99.7% of the world. The satellites communicate with each other with the mesh network protocol. You can pass a message in between the constellation of satellites to anywhere in the world.”

Enlarge

Enlarge

Enlarge

Enlarge

If the project is successful, it could not only change our Earthly system of communication, but it could also guide the design of future interplanetary communication arrays.

“Say we have a colony on Mars – you could have a similar satellite swarm surrounding Mars,” Liu says. “Then you could actually pass messages back and forth to colonists and astronauts when they have stronger radios and antennas.”

Liu’s project is called the “Distributed Universal Satellite Technology (DUST).” It’s done through the Sensor Network Laboratory and is part of the College of Engineering’s opportunities for students across the university every year. Liu’s project is funded by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). The project advisor is associate research scientist Darren McKague from Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering.

Currently, the team – which is comprised of nearly 30 students – is designing miniature satellites, called “CubeSats,” with a projected launch date of 2021 (although this is very tentative).

“The communications side is very new,” Liu says. “We have to make sure that the protocol works on the hardware and the hardware is supported by all of our other subsystems in the satellite. It’s cool being able to do stuff that no one has done before.”

It’s cool being able to do stuff that no one has done before.

Havel Liu, CE and ME undergraduate student

Enlarge

Enlarge

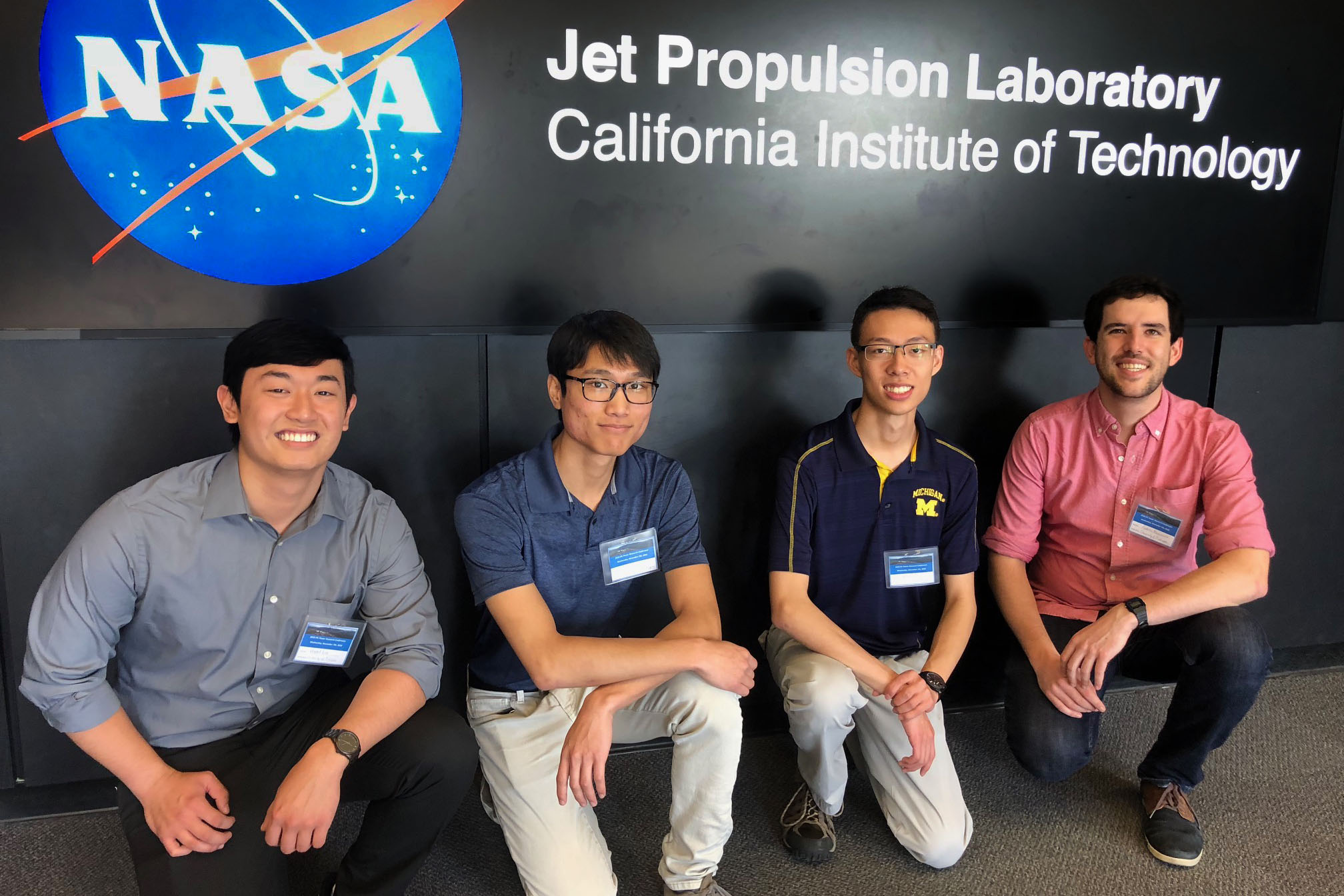

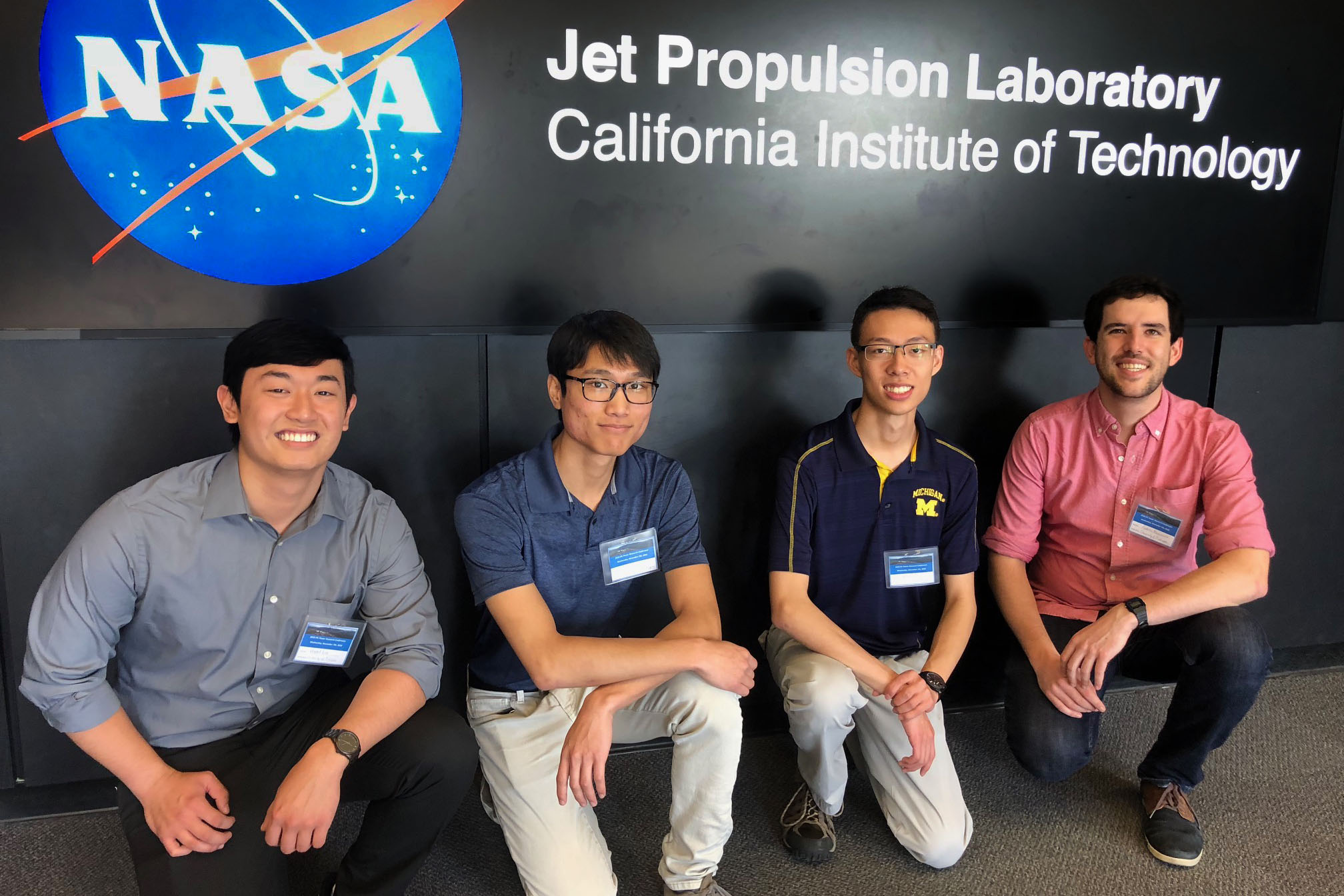

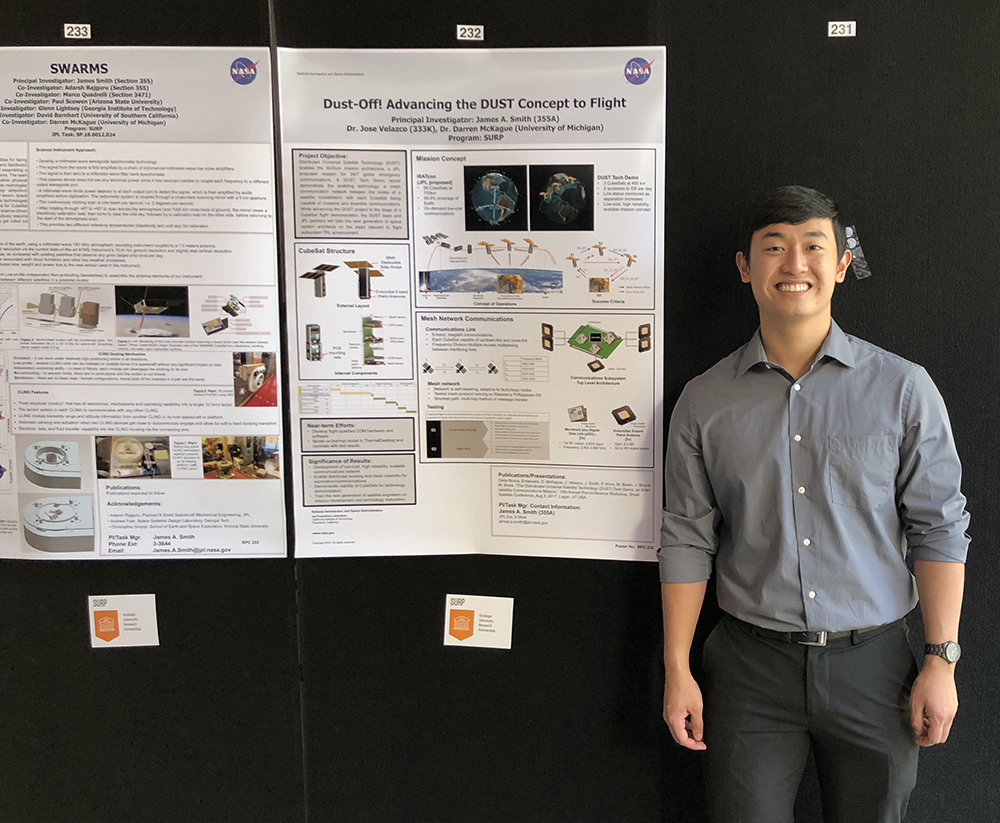

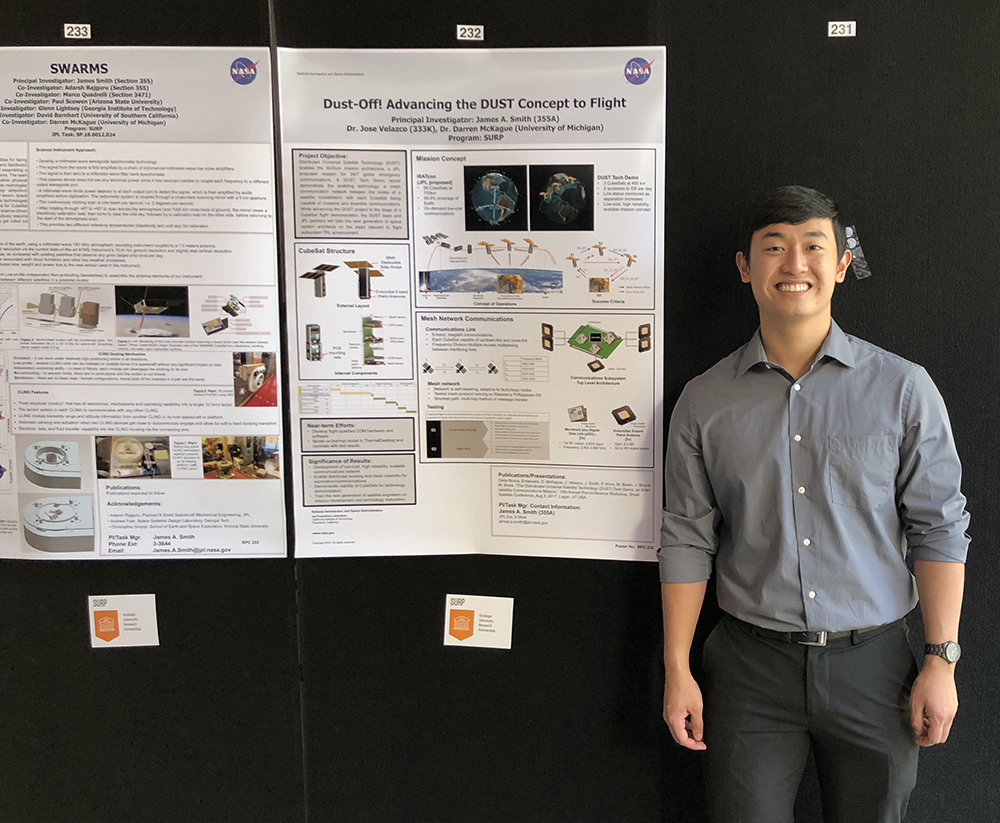

Liu and three teammates – Taylor Sun (BSE ME), Andres Penaranda (MSE AERO), and Jeff Yin (BSE CE) – recently presented the project at a JPL poster conference. The conference occurred in the center of JPL’s campus, and while it was a way for JPL to showcase its research, it was also an opportunity for Liu’s team to garner additional support for their project and make a case for more funding. The cost of the satellite construction and launch is well-beyond the funds they are currently given.

This project has inspired Liu to consider a career in space-oriented companies, like JPL and SpaceX, despite many of his friends wanting to work for Amazon or Microsoft. The opportunities for personal and professional growth afforded by the MDP is one of the reasons Liu is grateful he came to U-M.

“Michigan is one of the best universities for both research and just general academics, especially in engineering,” Liu says. “It’s hard to beat Michigan.”

MENU

MENU